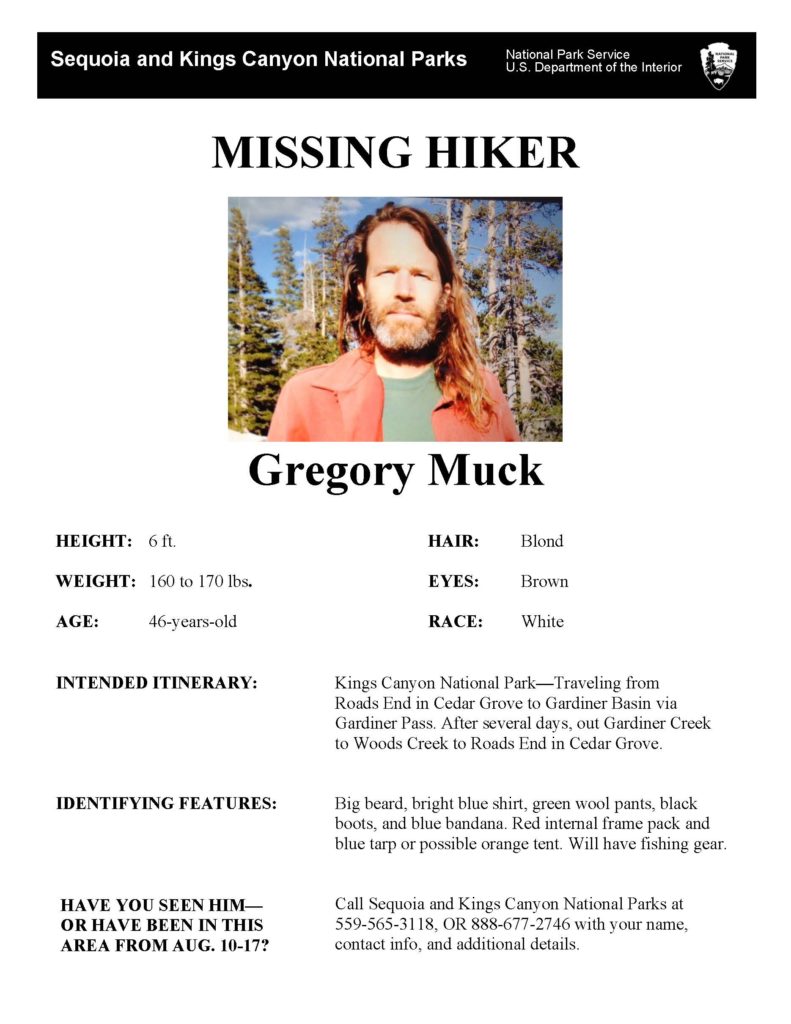

The smiling face of the man caught my eye. He looked happy. Somebody’s son, husband, father. The flyer looked tattered, and as I inspected it more closer, realized it had been up for several months. MISSING in big block letters screamed out from the top. The face in the photo was identified, with pertinent details of where and when they were last seen and who to contact with information. I am filled with a sense of sadness, realizing the likelihood that they are long gone.

The smiling face of the man caught my eye. He looked happy. Somebody’s son, husband, father. The flyer looked tattered, and as I inspected it more closer, realized it had been up for several months. MISSING in big block letters screamed out from the top. The face in the photo was identified, with pertinent details of where and when they were last seen and who to contact with information. I am filled with a sense of sadness, realizing the likelihood that they are long gone.

Hundreds of people go missing on public lands throughout the United States each year. Working at Rocky Mountain National Park, I became fascinated by a couple of books from the visitor center bookstore. Death, Despair and Second Chances in Rocky Mountain National Park details bizarre deaths, cases of missing people, and somewhat miraculous rescues when all hope is lost.

Some of the cases completely confounded me, particularly those having to do with children. Perhaps none more so than the story of a father and his young daughter on a church hike up Flattop Mountain. The young girl developed blisters and said she couldn’t go on. Dad told her to wait on the trail and he would get her on the return (does this really seem like a good idea?). During his descent, the child was gone, only to be found having fall down a cliff to her death.

Other cases were equally bizarre with people vanishing without a trace in a seemingly benign area. Nothing can be more gut wrenching for a family than to lose a family member to the wilderness with no clues as to how and why. With no closure, the pain of not knowing has to be unbearable.

I experienced this type of torture first hand my very first summer working at Sequoia National Park. The hundreds of miles of backcountry trails define Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks as true wilderness experiences. And assisting with this experience for backpackers are several back country rangers who live in cabins and patrol the remote areas of the park. That summer, one of the seasoned rangers of the back country, Randy Morgenson went missing while on patrol one day. Despite a long search involving his fellow rangers, no sign of him was ever found that year.

To this day, I remember seeing the flyers with his bearded face adorning the kiosks at every trail head, words detailing what he looked like, where he was last seen, pleading for information to be reported. The pall of the incident hung over the entire park staff that year. As weeks turned into months, rumors started to churn about his troubled marriage, with people speculating he had just disappeared to Mexico or parts unknown. I can only imagine how difficult this rumor-mongering must have been on his family.

Five years later, while living in Oregon, I happened to call my friend who I had worked with that first summer. Her voice sounded strange when she answered the phone.

“I can’t talk right now — there’s a bit of a crisis in the park, where I’m counseling staff.”

Before she could finish and get the words out of her mouth, I knew what she was going to say.

They’d found Randy.

He’d died while on patrol, swept down a stream where he wasn’t seen by the initial search and rescue. A hiker had found his uniform shirt, complete with his name tag and skeletal remains.

So how do you avoid becoming tomorrow’s story in the newspaper? The answers lie with keeping in mind your own safety from the moment you start planning a hike to the moment you get back to your car.

Too many people don’t consider worst case scenarios when they go out for a hike. That you get injured and be forced to spend the night. That you could get lost and run out of food. That your cell phone won’t work among the high peaks of the Rocky Mountains or the rugged canyons.

While working at Capitol Reef National Park, I used to go hiking every evening after work. Being the coolest part of the day, I enjoyed watching the setting sun illuminate the red rocks. Most of the time, I went by myself.

Not only did I let someone else know where I was going, but I would leave a colorful note on the front door of my park service apartment, with my hike route, and expected due date and time on it.

The pack I take with me during my patrols of the Indian Peaks weighs plenty even on the hottest days. Filled with compass, maps, whistles, extra food, water filter, jacket, matches — I know if the worst happened, I could survive the night.

Lastly, if you realize you’ve become lost, STOP. Sheer panic can drive people to do irrational, crazy things that only exacerbate the situation.

- Stop — just stop moving and sit down

- Think — consider your situation

- Organize your resources — do you have water? can you build a fire?

- Plan — come up with a plan — how can you be help yourself given the current circumstances?

There are few places that make me happier than to be outside recreating in the Rocky Mountains. By planning my adventures with careful preparation, I hope to be frolicking in the outdoors for many years to come.